In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Adaptive Immunity 2. Attributes of Adaptive Immunity 3. Components.

Meaning of Adaptive Immunity:

In contrast to innate immunity, vertebrate has a specific or adaptive immunity which is capable of recognising and selectively eliminating specific foreign microorganisms and molecules. This form of immunity develops as a response to infection and adapts to the infective agents, thus it is called adaptive immunity.

It is sometimes called acquired immunity to emphasise that this potent protective responses are “acquired” by experience.

The adaptive immune system is able to recognise and react to a large number of microbial and non-microbial substances. This immunity includes reactions to specific antigenic challenges. It has an extraordinary capacity to distinguish among different, even closely related microbes and molecules and for this reason it is also called specific immunity.

Attributes of Adaptive Immunity:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This immunity displays several characteristic attributes like:

(1) Specificity,

(2) Diversity,

(3) Immunologic memory,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(4) Specialisation,

(5) Self/non-self recognition, and

(6) Self- limitation.

(1) Specificity:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This property of immune system permits it to distinguish among different and even closely related molecules. Antibody, an effector molecule of adaptive immunity, can distinguish between two protein molecules that differ in only a single amino acid.

(2) Diversity:

Adaptive immunity is capable of generating tremendous diversity in its recognition of molecules, allowing it to recognise billions of uniquely different structures on foreign antigens. It is due to the variability in the structures of the antigen- binding sites of lymphocyte receptors for antigens.

(3) Immunologic memory:

One of the most important characteristic of adaptive immunity is the ability to remember and respond more vigorously to repeated exposures to the same antigen. Responses to second and subsequent exposures to the same antigen are called secondary immune responses. They are usually more rapid, larger and often qualitatively different from that of the first or primary immune response to that antigen.

Such memory occurs partly because each exposure to an antigen expands the clone of lymphocytes specific for that antigen. In addition, stimulation of naive lymphocytes by antigens generates long-lived memory cells. Because of this property, adaptive immunity may confer life-long immunity to many infectious agents after an initial encounter.

(4) Specialisation:

The adaptive immune system responds in distinct and special ways to different microbes, thus maximising the efficiency of antimicrobial defence mechanisms. The adaptive immunity is elicited by different classes of microbes or by the same microbe at different stages of infection and each type of immune response protects the host against that class of microbe.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(5) Self/non-self recognition:

The adaptive immune system has the ability to recognise, respond to, and eliminate foreign (non-self) antigens while not reacting harmfully to that of individual’s own (self) antigenic substances. Such unresponsiveness to self-molecules is called tolerance, which is maintained by several mechanisms.

Abnormalities in the induction or maintenance of self-tolerance lead to immune responses against self-antigens, often resulting in disorders called autoimmune diseases.

(6) Self-limitation:

The adaptive immune response wane with time after antigenic stimulation, thus returning the immune system to its resting basal state, a process called homeostasis. This is maintained because immune responses are triggered by antigens and function to eliminate the antigens, thus eliminating the essential stimulus for lymphocyte activation.

Therefore, antigens and the immune responses to them also stimulate regulatory mechanisms that inhibit the response itself.

These characteristics of adaptive immunity are necessary if the immune system is to perform its normal activities of host defence. Specificity and memory are required to mount heightened responses to persistant or recurring infections. Diversity is essential if the immune system is to defend individuals against innumerable pathogens.

Specialisation enables the host to “custom design” responses to best combat many types of microbes. Self-limitation allows to return to state of rest after the elimination of antigen and to be prepared to respond to other antigens. Self-tolerance is vital for preventing reactions against one’s own cells and tissues, while diversity enables the immune system to recognise different foreign antigens.

Components of Adaptive Immunity:

An effective adaptive immune response involves three major groups of cells of vertebrate body:

(i) Lymphocytes,

(ii) Antigen- presenting cells and

(iii) Effector cells.

(i) Lymphocytes:

The principal cells of adaptive immune system are lymphocytes. These are produced in the bone marrow by the process of haematopoiesis like most other blood cells. Lymphocytes specifically recognise and respond to foreign antigens.

These cells produce and display antigen-binding cell surface receptors and thereby mediate the defining immunologic attributes of adaptive immunity, viz. specificity, diversity, specialisation, memory and self/non-self recognition.

There are two major sub-populations of lymphocytes – B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes, which differ in their antigen recognition and function. B lymphocytes are the only cells capable of producing antibodies.

They recognise extracellular (including cell surface) antigens and differentiate into antibody- secreting cells, thus functioning as the mediators of humoral immunity. T-lymphocytes, the cells of cell-mediated immunity recognise antigens of intracellular microbes and function to destroy these microbes or the infected cells.

(ii) Antigen-presenting cells:

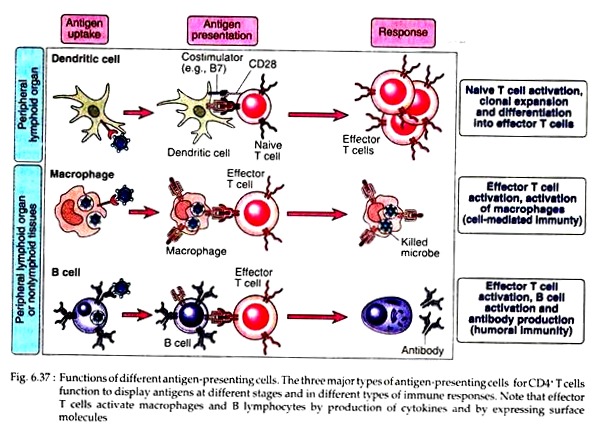

The initiation and development of adaptive immune response require that antigens be captured and displayed to specific lymphocytes. The cells that serve this function are called antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The most specialised APCs are dendritic cells, macrophages and B lymphocytes.

Dendritic cells capture microbial antigens that enter from the external environment, transport these antigens to lymphoid organs and present the antigens to naive T cells to initiate immune responses. Other cells function as APCs at different stages of cell-mediated and humoral immune responses.

These cells express class II MHC molecules on their membrane. Generally these cells first internalise antigen either by phagocytosis or by endocytosis and then display a part of that antigen bound to class II MHC molecule on their membrane (Fig. 6.37).

The TH cells then recognise and interact with the antigen-class II MHC molecule on the antigen presenting cells. Additional co- stimulatory signal is then produced by the APC, leading to activation of TH cells.

(iii) Effector cells:

The activation of lymphocytes by antigen leads to the generation of numerous mechanisms that function to eliminate the antigen. The cells that help in elimination of antigen are called effector cells. Activated T lymphocytes, mononuclear phagocytes and other leucocytes function as effector cells in different immune responses.

Lymphocytes are present in the blood. From the blood they can recirculate to lymphoid tissues. In anatomically discrete lymphoid tissues and organs, lymphocytes and other accessary cells are concentrated to interact with one another to initiate immune responses.