In this article we will discuss about the selfish behaviour seen in animals.

“Selfishness” has an unpleasant meaning and this word in sociobiology should not be taken at its face value. All that matters is that such behaviour benefits the individual doing it. It should be as noncontroversial as moving out from a burning house or coming into the shade out of the rain. In other words, selfish behaviours may also benefit others.

The selfish gene approach to ethology has been linked to the sociobiological notion that natural selection acts on genes that code for animal behaviour. From its (selfish gene) inception in 1976, Richard Dawkins himself has made it crystal clear that genes aren’t ‘selfish’ in any emotional or moral sense and have no inherent qualities of selfishness. In-fact genes are nothing but series of tiny bits of DNA put together, in a particular sequence, which are distinct from other such tiny DNAs.

Yet, genes can sometimes be treated as though they are selfish. This is because the process of natural selection favours those genes that codes for a trait that increases the fitness of its bearer above and beyond that of others in the population. Such genes will increase in frequency. Therefore, natural selection often (but not always) produces genes that appear to be selfish.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such approach — when applied particularly to animals’ social behaviour — lead to the ways in which ethologists think about genes and animal behaviour. Thus, the approach of a gene being “selfish” provides a convenient mean of conceptualizing some problems in animal behaviour.

In the animal world a number of such selfish behaviours are witnessed. One such is the warning or alarm call given by a chickadee when a hawk approaches a chickadee flock. One may think that the caller has put itself at risk to save its flock mate. It is possibly not so. For such behaviour (warning call), socio-biologists have put forward all sorts of individual advantages, such as:

1. In case the hawk is unable to stop unless vulnerable prey are visible, then the warning note helps the one who gives it to get its flock-mate out of danger.

2. In case the hawk is able to move on quickly unless it gets reinforcement in the form of food. Then, by giving the alarm call, the caller bird has helped itself by decreasing the chances of predation on its flock mates.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. According to Dawkins (1976), it may be that the call itself is less a warning to flock-mates than a signal to the predator that the bird giving the call has spotted the intruder and is, thus, a poor candidate for attack.

However, Klump (1986) have refuted the above point 3 by pointing out that the calls are audible only to flock-mates but not to approaching hawks, as the high pitched alarm notes of chickadees are above the frequencies at which the hawks hear.

Another such behaviour is stotting, a strange bounding movement shown by gazelles. Such movements might be a signal that the stotter is strong and healthy and likely to be hard for a predator to run down.

Another such example is the tail flagging signal given by the white-tailed deer by raising its tail to show its white underside. This is suggestive that the signal is meant for the predator, that it has been discovered.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such behaviours as given above is suggestive that the signals promote group movements that would discourage predation. One probable reason to believe the above is that the behaviour in both gazelles and deer occurs in quite young animals that are not matured enough to elude predators, but it might be helped by the presence of adults.

Therefore, this qualifies as selfish behaviour. It may also be significant that, among adults, tail flagging is frequent among groups of does (mothers, daughters and sisters) and less frequent among buck groups.

Another way to explain selfish behaviour in animals is in the form of cover-seeking in which each individual tries to reduce its chances of being caught by a predator. Such a case has been observed by Hamilton (1971) in a hypothetical city pond where a predator snake and some frogs live.

The snake most of the time stays at the bottom of the pond and feeds at a certain time of the day. The frogs, in order to escape, climb out on the edge of the pond before the snake starts to hunt.

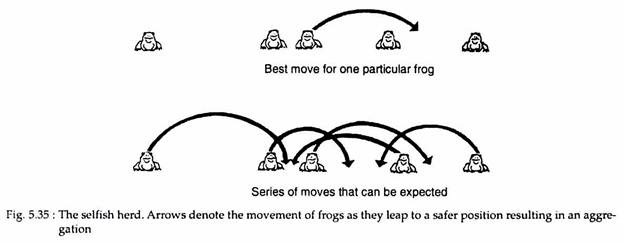

They, however, do not move inland from the rim of the pond due to the presence of more threatening terrestrial predators. The snake at some unpredictable place surfaces and grabs the nearest frog. Each frog, thus, to minimise its chances of being eaten, will jump around the rim moving into the nearest gap between two other frogs. The end result will be an aggregation as shown in Fig. 5.35.

More such examples of selfish herd can be applied to herds of ungulates, flocks of birds and school of fishes. When each individual behaves in such a selfish manner and minimizes its chances of being picked off, then the group as a whole may be more vulnerable since the predator can go after the group rather than on a single dispersed individual.