In this article we will discuss about the meaning and nature of climax community.

Meaning of Climax Community:

Climax community is the stable end product of successional sequence or sere. It is a community that has reached a steady state of species composition, structure and energy flow, under a particular set of environmental conditions. Steady state indicates the dynamic nature of the climax.

Also the end of successional change does not mean that community development has come to an end. As has been stated above, climax community is always in a state of flux and its structure undergoes changes due to birth, death and growth processes. However, these changes are less dramatic than the community transformations observed during succession.

The characteristics of a climax community are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. The climax community is able to tolerate its own reaction.

2. It tends to be mesic (medium moisture content) rather than xeric (dry) or hydric (wet).

3. The climax community is more highly organised.

4. The climax community with its more complex organisation has large number of species and more niches.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. The organisms of earlier successional stages tend to be smaller, shorter-lived with a higher biotic potential (r-selected). In contrast, the species of climax community tend to be relatively large, long lived and with a low biotic potential (K-selected).

6. In climax community, energy is at a steady state (net primary production is zero), whereas, in immature stage of succession, gross primary production tends to be greater than community respiration, signifying accumulation of energy.

7. Immature ecosystems are temporary while in climax community the stability is high.

8. Climax communities show less broader changes and are more resistant to invasions than immature ecosystems.

Nature of Climax Community:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A. Mono-climax and poly-climax:

According to Clements (1916) succession resulted in a single true climax community, determined primarily by the climate of the region. This view of his is called the mono-climax theory of succession, which elaborates that the many different vegetation communities found in a region are successional stages of the true climax community.

These different vegetation communities were often called subclimax, pre-climax or post-climax communities. This theory further stresses that, given sufficient time, the difference in local conditions of soil moisture, temperature, nutrient availability, hydrology and so on (that give rise to different vegetation types) would be overcomed and a homogeneous true climax would develop.

Many observations seem to conflict this hypothesis as it is evident that even under primeval conditions it was difficult to find large areas of uniform vegetation. Rather, it is appropriate to recognise several different communities as climax.

Poly-climax theory of succession stresses that many different types of vegetation form the climax community, depending on local conditions. The climax community should be in harmony with the whole environment and not just climate. However, the hypothesis of poly-climax is also basically terminological.

B. Climax pattern theory:

More recently a third hypothesis was proposed by Robert H. Whittaker (1953) known as climax pattern theory, which rejects the classification approach. It recognises a regional pattern of open climax communities whose composition at any particular locality depends on the specific environmental conditions present at that time.

The climax pattern concept, in a sense, views only one big community that changes according to soil, slope and other habitat factors. This approach is considered to be more useful and closer to reality to describe such pattern of variation.

Factors Determining the Nature of Climax Community:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Many factors such as soil nutrients, moisture, slope, exposure etc. determine the nature of the climax community. Fire is another important feature of many climax communities. Fire-resisting species are favoured while other species that would have dominated are excluded. Fire triggers the release of seeds in some pine species. After the fire has receded the pine seedlings grow rapidly in the absence of competitors.

Grazing pressure is another factor that determines the nature of climax community. Intense grazing may turn grassland into shrub-land. Shrubs and cacti may establish themselves as they are unsuitable for forage. The grazing of many herbivores may suppress many species of plants and favouring competitors that are less desirable as food.

Transient and cyclic climax:

Once the climax community has established itself, its general appearance does not change in spite of the constant replacement of individuals within the community. However, all climaxes do not persist for ever. A stable climax community is not possible for long, as natural disturbances like storms; fire, cold waves, season etc. have detrimental effects.

Non- successional, short term, reversible changes in the floristic and faunal composition (or fluctuations) of a community are also common. These, are said to be cases of transient climax. Transient climaxes develop on ephemeral resources and habitats such as temporal ponds and carcases of animals.

The development of animal and plant communities in seasonal ponds is a simple case of transient climax. Pond waters either dry up in summer or freeze solid in winter, thereby regularly destroying the communities. These communities reestablish each year during the growing season from the pores and resting stages left by plants, animals and microorganisms.

Another example is the excreta and carcasses of dead organisms. They are resources for a wide variety of detritus feeders and scavengers. The dead body of a large animal is fed upon by a succession of vultures in African savannas. First, the large, aggressive species eats the largest masses of flesh, followed by smaller species that picks smaller bits of meat from the bones.

Finally, another kind of vulture invades the area that cracks open the bones and feeds on the bone marrow. Later scavenger mammals, maggots, micro-organisms enter the area and ensure that nothing edible remains. When the feast is concluded all the scavengers disperse. Thus, no climax is present in this sort of succession or we may consider all the scavengers as a part of a climax.

A few dominant species in a few simple communities may create a cyclic climax. Cyclic climax develops where each species become established only in association with some other species. The change in cyclic pattern occurs due to the life cycle of dominant species.

Stable cyclic climaxes usually follow a cyclic pattern often with one of the stages being bare substrate. Harsh physical conditions, such as frost, strong winds etc. result in cyclic climaxes.

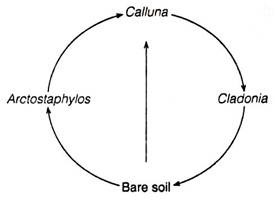

Examples of cyclic vegetation changes was studied by Watt (1947). Watt found that the dwarf Calluna heath in Scotland was the dominant shrub. It looses its vigor as it ages and is invaded by the lichen, Cladonia. The lichen mat dies in time to leave bare ground.

This bare area is invaded by bearberry (Arctostaphylos). It is, in turn, invaded by Calluna. Calluna is the dominant plant, while Arctostaphylos and Cladonia are allowed to occupy the area that is temporarily vacated by Calluna.

Thus, the life history of this dominant plant controls the cyclic sequence:

The concept of climax community incorporates cyclic patterns of change and mosaic patterns of distribution. The climax is a dynamic and self-everlasting state. Persistence is the key to climax. In a climax community, all species (including dominant species), are continually able to reproduce successfully and persists in a uniform climatic area.