In this article we will discuss about the Fossorial Adaptation:- 1. Meaning of Fossorial Adaptation 2. Classification of Fossorial Adaptation 3. General Modification 4. Some Examples.

Meaning of Fossorial Adaptation:

The adjustment of animals through their anatomical and physiological modification to the subterranean environment is known as fossorial adaptation. Generally, environment acts upon animals to modify the structural designs.

But in fossorial adaptation the animals change the environments by making a subterranean zone through digging of its own. Hence by the influences of environments as well as animals itself, adaptive changes are acquired.

Classification of Fossorial Adaptation:

Fossorial animals may be classified into three categories:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Animal digging the soil for food:

They are considered as a first step towards fossorial form. They dig the soil by snout or tusk, e.g., elephant, swine, etc. Apart from this, there is but little fossorial adaptation that can be noted. In elephants, the entire modification of skull is for digging mechanism.

ii. Animals digging for retreats but seek their food above the ground:

These are the next forms whose limbs become shorter but they have no extreme modifications, e.g., fox, mongoose, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Animals digging for retreat but find their food under the ground:

They have got extreme modification for fossorial life, e.g., Talpa sp., Rattus etc.

General Modification for Fossorial Adaptation:

Body contour:

Body is fusiform or spindle shaped which form less resistance in the short subterranean passage. The back portion of shoulder girdle is the widest part of the body. This is true in case of mole while in Echidna and Platypus, no extreme modification is seen. Some legless forms are present, e.g., limbless lizards, snakes, caecilians, etc., whose body is cylindrical.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Head:

Head is tapering, which causes the skull to become conical (e.g., spiny ant-eater, moles and shrews). The jaws with feeble musculature are present in these creatures to act upon feeble pray.

Neck:

Neck in burrowing animals is either absent or is very short. In moles, the second, third and fourth cervical vertebrae are ankylosed.

Eyes:

Through constant disuse, eyes become non-functional. For example, small eyes are present in pocket-gophers and others; mere spot in the muscle is found in mole-rat (Spalax typhus); imperfectly developed eyes are present in marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops); very minute eyes are present in Talpa; while in gold mole (Chrisocloris) eyes are covered with skin.

If the eyes were well developed then it would have been a point of frequent injury in burrowing animals.

Ear:

As an ‘auditory receptor ears losses its importance. Therefore, it becomes inconspicuous, e.g., very small and minute ear is present in Geomydae, rattle snake and others; ear is represented by a fringe of skin in cape golden mole; ear is completely absent in fully fossorial form monotremes and moles. External ear tends to disappear, as they would be a hindrance for burrowing animals.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Tactile Organs:

To compensate the loss of audiovisual receptors, tactile organs are highly developed. In addition to tail, snout in mole is richly innervated and acts as highly sensitive tactile organ.

Tail:

Long tail is an inconvenient organ for fossorial life. Firstly, it takes some extra space and secondly, it helps predators to catch the pray from hideout. So, tail becomes shorter. Where present, it acts as a tactile organ, e.g., hedgehog, rattle, woodchuck. In wombat it is vestigial whereas reduced in several moles. Comparatively larger tail is present in some large fossorial mammals.

Digging Mechanism and Subsequent Modifications:

Snout:

Snout is truncated and upturned at the tip, which helps in digging mechanism. A pre-nasal bone develops at the tip of the nasal cartilage, which reinforce in digging e.g., swine and Talpa.

Incisor Teeth:

The incisor teeth are upturned protruded and helps in digging in pocket gopher. The tusks in elephant also help in digging.

Canine Teeth:

In swine, canines are effective digging instrument and in others it becomes reduced.

Forelimbs:

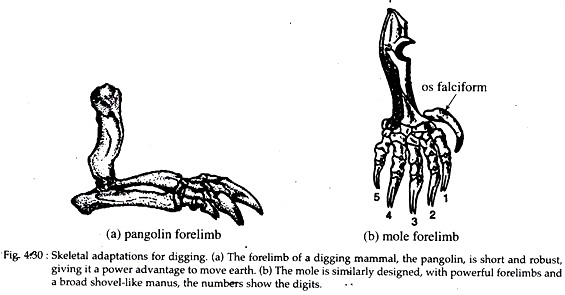

As long limbs create problem in short subterranean passage, the limbs become shorter. The bones of fore limbs become short and stout (Fig. 4.30) for attaining speed in semi-fossorial animals, e.g., hare, pig-footed bandicoot.

The olecranon process of ulna is very well developed. The palm becomes broadened by an additional bone, along with the original five fingers, which is known as osfalciformi (Fig. 4.30b). The second and third fingers of the fore limbs become greatly enlarged and bear claws in Chrisocloris sp.

Pectoral Girdle:

The pectoral sockets tend to come nearer. This makes the shoulder narrow and helps in entering through the narrow passage of the burrow.

Narrowing of shoulder can be formed by any of the two processes — either by shifting the whole pectoral girdle towards the neck, e.g., mole and monotremes, or by hollowing of the thoracic cavity as the ribs and sternum become inwardly convex instead of outwardly, e.g., golden moles.

Clavicle extends from the pectoral socket to the episternum. A T-shaped episternum is present in monotremes. Coracoid is present as a process from scapula.

Muscular Attachment:

Large tuberosities develop at the proximal part of the limbs for muscular attachment. Great ridges develop at the proximal part of the humerus for the attachment of strong shoulder muscles, which help in rotating the limbs. The olecranon process, which is the extension of the ulna, is for the insertion of triceps muscle.

Hind limbs:

The hind limbs are not as robust as the fore limbs. In femur, prominent tuberosities develop for muscular attachment. Tibia, fibula and calcaneum become fused for greater leverage. A large sesamoid bone develops as an outgrowth of tibia, e.g., Talpa. An unusual extension of bone from fibula develops for better muscular attachment.

Pelvic girdle:

Ileum and ischium develop parallel to the vertebral column. Ischium becomes fused to the sacrum.

Functions of the Limbs:

The architecture of the strong fore limbs is well suited for digging into the soil. Its claw and musculature help in cutting and digging the soil. The broad palm acts as a big axe to loose maximum soil at a time.

The fore limbs dig the soil while the hind limbs throw them out. The fore limbs are stronger than hind limbs in digging and the hind limbs are stronger than fore limbs in pushing the animal forward and in prevention of backward thrust.

Parallel Features of the Fore and Hind Limbs:

i. Large sesamoid bone at the side of the tibia of mole can be comparable to the Os falciforme of hand.

ii. Unusual extension of the proximal end of the fibula beyond the articulation may be comparable to the olecranon process of the elbow.

Sacral and Lumbar Bones:

The vertebrae of sacral and lumbar regions are fused for greater rigidity. Firm fusions of the sacral and lumbar vertebrae give greater strength and firmness in pulling the animal through the earth. The transverse process of lumbar vertebrae and the muscles which are attached to them are comparatively weak because the maximum pressure comes longitudinally instead of laterally.

Hibernation:

This is a special feature among the fossorial animals living away from the tropics. They have to hibernate, i.e., go for long sleep in winter due to lack of food during extreme cold. Simultaneously, it is very tuff to dig into the frozen soil.

Some Examples of Fossorial Vertebrates:

Class Osteichthyes:

Spiny eel (Mastacembelus), cuchia (Amphipnus), mud eel (Symbranchus)

Class Amphibia:

Caecilians

Class Reptilia:

Tuatara (Sphenodon), spiny lizard (Uromastix), legless lizards (Ophisaurus, Rhineura) and desert snakes (‘Crotalus, Pituphis).

Class Aves:

Burrowing owl, cliff swallow, starlet etc.

Class Mammalia:

All wholly fossorial mammals are primitive, small, plantigrade, basically pentadactyle with moderate to large claws, and relatively defenseless.

Order Monotremata (entire order).

Order Marsupialia e.g., Wombat, dasyurus, pig footed bandicoot (Chaeropus), marsupial mole (Notoryctes), kangaroo rat (Bettongia).

Order Edentata e.g., Armadillos.

Order Insectivora e.g., Moles, golden mole, water shrew (Crossopus), hedgehog (Erinaceus), shrew mole (Scalopus).

Order Rodentia e.g., hares (Lepus), ground squirrels, wood chuck, pocket gopher, mole rats, bamboo rat etc.

Order Carnivora e.g., Otter (Lutra), rattel, Javanese skunk, American badger.

Cohort – Ungulata – Few dig for food (Swine, elephants).