In this article we will discuss about Honeybee:- 1. Different Species of Domesticated Honeybee 2. Colony Composition of Honeybee 3. Life History 4. Bee Language.

Different Species of Domesticated Honeybee:

In Europe and America the species universally managed by bee-keepers is the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera). This species has several subspecies or regional varieties, such as the Italian bee (Apis mellifera ligustica), European dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera), and the Carniolan honeybee (Apis mellifera carnica). In the tropics, other species of social bee are managed for honey production, including Apis cerana.

Non-Apis Bees :

In North America, efforts have focused on the development of non-Apis species with significant success for the alkali bee, Nomia melanderi, various mason bees, Osmia spp., and the alfalfa leafcutter bee, Megachile rotundata.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Among these, alkali bees and mason bees are successfully cultured, but for the alfalfa leafcutter bee, the detailed studies necessary to successfully integrate a native bee into a sustainable agricultural system has remained unattended.

Colony Composition of Honeybee:

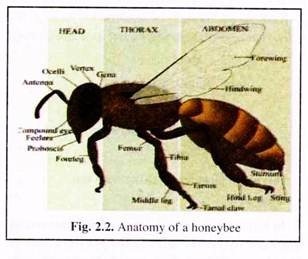

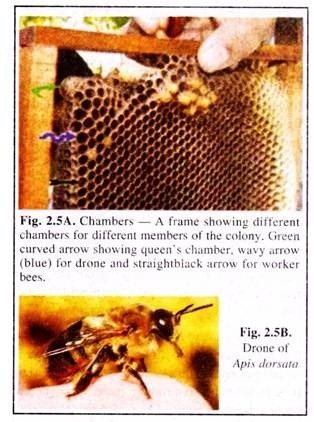

Its colony contains one queen bee (fertile female); a few thousand drone bees or fertile males; and a large population of sterile female or worker bees. Anatomical terminologies for different external organs of a bee is given in Figure 2.2.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Queen Bee:

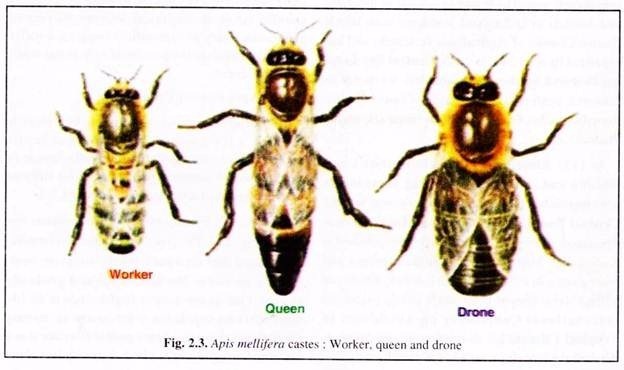

Usually every beehive contains one queen (Fig. 2.3). The size of the queen is comparatively larger than the other types. Its wings are smaller than its body. The abdominal end gradually tappers. One queen usually flights once in its life time, either for copulation or for swarming. Its only function is to lay eggs.

Some people consider it as a machine for egg laying in a hive. It usually lays about 1500-3000 eggs per day, which includes both fertilised and unfertilised eggs. Unfertilised eggs give rise to drones, and workers are developed from fertilised eggs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A virgin queen develops from a fertilized egg The queens are prepared from the fertilized eggs according to the requirement of the colony by feeding special types of food called Royal Jelly, a protein-rich secretion from glands on the heads of young workers.

If the queen larva is not fed heavily with royal jelly, then it develops into a regular worker bee. All honey bee larvae are fed with royal jelly for the first few days after hatching but only queen larvae are fed on it exclusively throughout. As a result of the difference in diet, the queen will develop into a sexually mature female, unlike the worker bees.

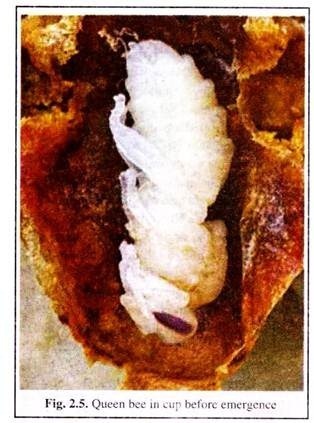

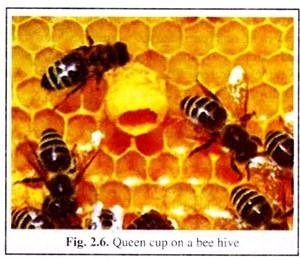

Queens are raised in specially constructed queen cells. The fully constructed queen cells have a peanut-like shape and texture. Queen cells start out as queen cups. Queen cups are larger than the cells of normal brood comb and are oriented vertically instead of horizontally.

Worker bees will build up the queen cup after the queen has laid an egg in a queen cup. In general, the old queen starts laying eggs into queen cups when conditions are right for swarming or supersedure. Swarm cells hang from the bottom of a frame while supersedure queens or emergency queens are generally raised in cells built out from the face of a frame.

As the young queen larva pupates with her head down, the workers cap the queen cell with beeswax. When ready to emerge, the virgin queen will chew a circular cut around the cap of her cell. Often the cap swings open when most of the cut is made, so as to appear like a hinged lid.

During swarming season, the old queen will leave with the prime swarm before the first virgin queen emerges from a queen cell.

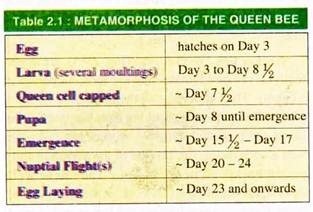

A time frame of queen bee’s developmental stages is given in Table 2.1.

Virgin Queen Bee:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A virgin queen is a queen bee that has not mated with a drone. Virgins are intermediate in size between workers and mated queen or laying queens, and are much more active than the latter. Virgin queens have little queen pheromone and often do not appear to be recognised as queens by the workers.

A virgin queen in her first few hours after emergence can be placed into the entrance of any queen-less hive or nuc and acceptance is usually very good. Whereas if a mated queen is placed into the entrance of any queen-less hive, it is repulsively recognised as a stranger and runs a high risk of being killed by the older workers.

When a young virgin queen emerges from a queen cell, she generally seeks out virgin queen rivals and attempts to kill them. Virgin queens will quickly find and kill (by stinging) any other emerging virgin queen (or be dispatched themselves) as well as any unmerged queens.

Queen cells that are cut on the side indicate that a virgin queen was likely killed by a rival virgin queen. When a colony remains in swarm mode after the prime swarm has left, the workers may prevent virgins from fighting and one or several virgins may go with after-swarms. Other virgins may stay behind with the remnant of the hive. As many as 21 virgin queens have been counted in a single large swarm.

When the after-swarm settles into a new home, the virgins will then resume normal behaviour and fight to the death until only one remains. If the prime swarm has a virgin queen and the old queen, the old queen will usually be allowed to live.

The old queen continues laying. Within a couple of weeks she will die a natural death and the former virgin, now mated, will take her place. Unlike the worker bees, the queen’s stinger is not barbed. The queen can sting repeatedly without dying.

Piping:

Piping describes a noise made by virgin and mated queen bees during certain times of the virgin queens’ development. Fully developed virgin queens communicate through vibratory signals: quacking from virgin queens in their queen cells and tooting from queens free in the colony, collectively known as piping.

A virgin queen may frequently pipe before she emerges from her cell and for a brief time afterwards. Mated queens may briefly pipe after being released in a hive.

Piping is most common when there is more than one queen in a hive. It is postulated that piping is a form of battle cry. This is the announcement of competing queens and the workers for their willingness to fight. It may also be a signal to the worker bees which queen is the most worthwhile to support.

The piping sound is a G or A frequency of pitch. The adult queen pipes for a two-second pulse followed by a series of quarter-second toots. The queens of Africanized bees produce more vigorous and frequent bouts of piping.

2. Drone Bee:

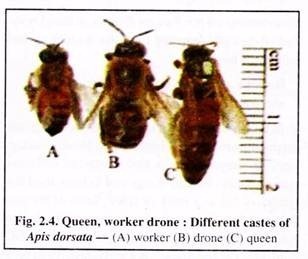

Drone or male bees (Fig. 2.4B) are the idlest of the three members of the colony. Their only work for the colony is to fertilize the female. These are somewhat larger in size and stouter than the workers, with powerful wings. They have greatly enlarged eyes, which cover most of the surface of the head.

Abdomen of a male is blunt and flat. They do not possess any proboscis for pollen collection. Their tongue is developed for gathering nectar. They have no wax-producing gland. After 10 days of emergence from the cocoon they can fertilize the female.

They can survive for 12 to 16 weeks. Not all but only some of the many male members can fertilize a female/ queen. However, the males, which succeed to copulate die after copulation. Rest members remain for next chance in the hive and maintain the population balance of the hive. In a hive, they appear most plentifully in the early summer at swarming time, after which the workers try to drive them out of the hive.

3. Worker Bee:

Worker bees (Fig. 2.4A) are imperfectly developed females and are most numerous in a colony. They undertake all the household works of a hive. These are small bees but have very well-developed and powerful wings. A worker bee possesses wax glands on the ventral side of the abdomen and a pollen basket on her hind-legs.

They have well- developed mandibles for work in the hive. A full- fledged sting is present in the last abdominal segment for protection as well as attack. However, these stings are for single use. If it is used, the bee will die immediately. Normally, the worker’s ovaries are small and non-functional, and the spermatheca is rudimentary. But it is evident that if required a worker bee can lay eggs for the sake of the hive.

Life History/ Cycle of the Honeybee:

The honeybee is a eusocial insect. Its colony contains one queen bee or fertile female; seasonally up to a few thousand drone bees or fertile males; and a large seasonally variable population of sterile female worker bees.

Details vary among the different species of honeybees, but common features in honeybees life history include:

(1) Virgin queens go out on Nuptial flights or mating flights away from their home colony and mate with multiple drones before returning either to the existing colony or fly outside to start a new colony. The drones die in the act of mating.

(2) Eggs are laid singly by the queen after mating flight, in a cell of the wax honeycomb, produced and shaped by the worker bees.

(3) Using her spermatheca, the queen actually can choose to fertilize the egg she is laying, usually depending on what cell she is laying.

(4) Drones develop from unfertilized eggs and are haploid, while females (queens and worker bees) develop from fertilized eggs and are diploid.

(5) Larvae are initially fed with royal jelly produced by worker bees, later switching to honey and bee bread or bee pollen. The exception is a larva fed solely on royal jelly will develop into a queen bee.

(6) The larva undergoes several moultings before spinning a cocoon within the cell and pupating.

(7) Young worker bees clean the hive and feed the larvae.

(8) When their royal jelly producing glands begin to atrophy, they begin building comb cells. They progress to other colony tasks as they become older, such as receiving nectar and pollen from foragers and guarding the hive.

(9) Later still, a worker takes her first orientation flights and finally leaves the hive and typically spends the remainder of her life as a forager.

(10) Worker bees cooperate to find food and use a pattern of “dancing” (known as the bee dance or waggle dance) to communicate information regarding resources with each other. This dance varies from species to species, but all living species of Apis exhibit some form of this behavior. If the resources are very close to the hive, they may also exhibit a less specific dance, commonly known as the Round Dance.

(11) Honeybees also perform tremble dances which recruit receiver bees to collect nectar from returning foragers.

Swarming:

New colonies are established by groups of bees known as swarms which consist of a mated queen and a large contingent of worker bees. This group moves en masse to a nest site that has been scouted by worker bees beforehand, this movement is called swarming.

Once they reach the new site, they immediately construct a new wax comb and begin to raise new worker brood. Usually, stingless bees start new nests with large numbers of worker bees, but the nest is constructed before a queen is escorted to the site and this initial worker force is not a true swarm.

History of Wild Honey Harvesting:

Collecting honey from wild bee colonies is one of the most ancient human activities and is still practised by aboriginal societies in parts of Africa, Asia, Australia and South America. Before the discovery of artificial culture method in India, people usually went to the forest for collecting honey.

Till now it is reported that several people are lost during collection of honey from the dense forest of Sunder- bans and other forests, perhaps devoured by Royal Bengal Tigers or crocodiles. Gathering honey from wild bee colonies is usually done by subduing the bees with smoke and breaking open the tree or rocks where the colony is located, often resulting in the physical destruction of the nest location.

History of Domestication of Wild Bees:

In India report of domestication of honey bees were found in prehistoric epics. At some point humans began to domesticate wild bees in artificial hives made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, pottery vessels and woven straw baskets or “skeps”.

Honeybees were kept in Egypt from antiquity. On the walls of the Sun temple of Nyuserre Ini, before 2422 B.C, workers are depicted blowing smoke into hives as they are removing honeycombs.

In ancient Greece, aspects of the lives of bees and bee-keeping were discussed at length by Aristotle. It is reported from prehistoric Greece (Crete and Mycenae) that there existed a system of high-status apiculture. It is found from the early writings that the hives, smoking pots, honey extractors and other beekeeping paraphernalia in Knossos were regularly used.

Bee-keeping was considered a highly valued industry controlled by bee-keeping overseers. Bee-keeping was also documented by the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and Columella.

Archaeological finds relating to bee-keeping have been discovered at Rehov, a Bronze and Iron Age archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Thirty intact hives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were discovered by archaeologist, Amihai Mazar, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the ruins of the city, dating about 900 B.C.

The hives were found in orderly rows of three feet high, in a manner that could have accommodated around 100 hives. This apiary could hold more than 1 million bees.

It had a potential annual yield of 500 kilograms of honey and 70 kilograms of beeswax (according to Mazar). It is also in evidence that an advanced honey industry existed in ancient Israel 3,000 years ago. Ezra Marcus, an expert from the University of Haifa, said the finding was a glimpse of ancient beekeeping seen in texts and ancient art from the Near East.

History of Study of Behaviour and Biology of Honey Bees:

It is revealed from the record that European natural philosophers undertook the scientific study of bee colonies since 18th century to understand the complex and hidden world of bee biology.

Prominent among these scientific pioneers were Swammerdam, Rene Antoine Ferchault de Reaumur, Charles Bonnet, and the blind Swiss scientist Francois Huber. Swammerdam and Reaumur were the first who intended to understand the internal biology of honeybees.

Reaumur at first constructed a glass-walled observation hive to observe activities of bees within hives. He observed queens laying eggs in open cells, but still had no idea of how a queen was fertilized.

As nobody had ever witnessed the mating of a queen and drone and many theories held that queens were self-fertile. Some others believed that a vapour or miasma emanating from the drones fertilized queens without direct physical contact.

Bee Language/ Foraging:

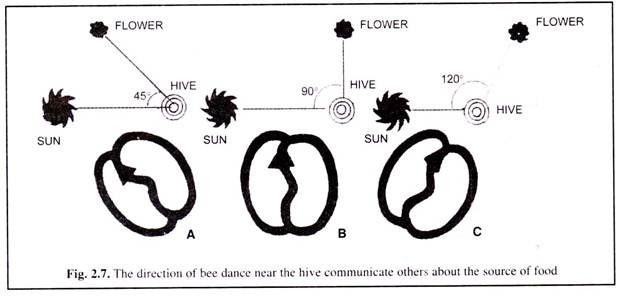

Some scout bees set out in the morning for foraging. On locating good sources of nectar (i.e., flowers) they return to their hive and perform characteristic movements (bee dances) at/near the comb (Fig. 2.7).

In bee dance the middle course of the dance communicates to the other bees the angle from the hive with reference to the sun. Taking a hint from this angle they have to fly to reach the food source. After getting the information more and more worker bees are deployed in food gathering.

The workers visit flower to flower, collect nectar and pollen and return to their own nest. During return journey they take clue from the position of the sun as well as by certain amount of memory. Finally, from the smell of their own hive they ascertain the landing place.