In this article we will discuss about the diseases found in bees:- 1. Bacterial Diseases 2. Fungal Diseases 3. Viral Diseases 4. Protozoan Diseases.

Bacterial Diseases:

1. American foulbrood disease (AFB):

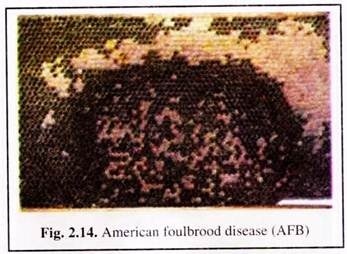

Bee- keepers generally regard American foul brood (AFB) as possibly the most destructive microbial disease (Fig. 2.14) affecting bee brood. The disease did not originate in, nor is it confined to America. It is widely distributed wherever colonies of Apis mellifera are kept.

In tropical Asia, where sunlight is abundant and temperatures are relatively high throughout the year, the disease causes severe damage to bee colonies. The disease is contagious and the pathogenic bacterium can remain dormant for more than 50 years.

Cause:

American foulbrood disease is caused by a spore-forming bacterium, Paenibacillus larvae, which only affect bee brood; adult bees are safe from infection. The disease spread quickly within the colony and can spread to other colonies. Natural transfer mainly takes place within a radius of 1 km around the apiary.

Symptoms:

At the initial stage of AFB infection, isolated capped cells from which brood has not emerged can be seen on the comb. The caps of these dead brood cells are usually darker than the caps of healthy cells, sunken and often punctured. On the other hand, the caps of healthy brood cells are slightly protruding and fully closed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As the disease spreads within the colony, a scattered, irregular pattern of sealed and unsealed brood cells (Fig. 2.14) can be easily distinguished from the normal, compact pattern of healthy brood cells observed in healthy colonies.

Control:

A ‘search and destroy’ strategy may be adopted in an attempt to minimize damage to apiaries. The procedure involves regular hive inspections by qualified apiary inspectors. The entire honeybee population that is infected by American foulbrood is killed and hive materials belonging to the colony, are disinfected or destroyed by burning.

The bees are usually killed by poisonous gas such as the burning of sulphur powder. The plastic hives should be cleaned and brushed with 3 to 5 per cent sodium hydroxide.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Chemotherapeutic methods of controlling AFB involve the administration of antibiotics or sodium sulfathiazole, in various formulations and is fed mixed with powdered sugar or sugar syrup. Antibiotics and sulfonamides prevent multiplication of the agent, though it will not kill the spores. Therefore, multiplication may begin again shortly after treatment. So the treatment must be repeated in much shorter intervals.

2. European foulbrood disease (EFB):

The range of distribution of European foulbrood disease is not confined to Europe alone and the disease is found in all continents where Apis mellifera colonies are kept. Reports from India indicate that A. cerana colonies are also subjected to EFB infection.

The damage inflicted on honeybee colonies by the disease is variable. EFB is generally considered less virulent than AFB; although greater losses in commercial colonies have been recorded in some areas resulting from EFB.

Cause:

The pathogenic bacterium of EFB is Mellissococcus pluton. It is lanceolate in shape and occurs singly, in chains of varying lengths, or in clusters. The bacterium is Gram-positive and does not form spores.

Symptoms:

Honey bee larvae killed by EFB are younger than those killed by AFB. Generally, the diseased larvae die when they are four to five days old, or in the coiled stage. The colour of the larva changes as it decays from shiny white to pale yellow and then to brown.

A sour odour can be detected from the decayed larvae. Another symptom that is characteristic of EFB is that most of the affected larvae die before their cells are capped. The sick larvae appear somewhat displaced in the cells.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Control:

The choice of an EFB control method depends on the strength of the infection, i.e., how many brood cells and combs are infested. If the infection is weak, the change of hygiene behaviour of the bees by placing the hive to a good foraging site can control the disease.

A better result is achieved if the individual combs are sprayed with a diluted honey solution. If the infestation is stronger, removal of number of pathogens in the colony will give good result. Since the bees’ hygiene behaviour is genetically determined, replacement of the queen is possible.

Re-queening can strengthen the colony by giving it a better egg-laying queen, thus increasing its resistance to the disease and interrupting the ongoing brood cycle giving the house bees enough time to remove infected larvae from the hive. Sometimes chemotherapeutic measures such as application of antibiotics are called for, however, their application, always risks the danger of residues.

Fungal Diseases:

Chalkbrood disease:

In Asia, Japan, temperate America and Europe the disease has been reported to cause serious problems to bee-keepers.

Cause:

Chalkbrood is a disease caused by the fungus Ascosphaera apis. It affects honeybee brood. This fungus only forms spores during sexual reproduction. Infection by spores of the fungus is usually observed in larvae that is three to four days old. The spores are absorbed either via food or by the body surface.

Symptoms:

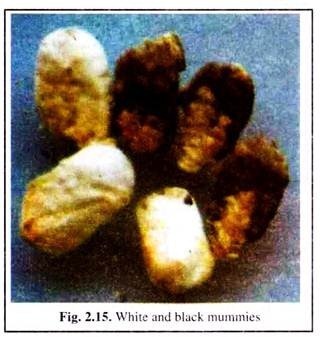

Initially the dead larvae swell to the size of the cell and are covered with the whitish mycelia of the fungus. Subsequently, the dead larvae mummify, harden, shrink and appear chalk-like. The colour of the dead larvae varies with the stage of growth of the mycelia: first white, then grey and finally, when the fruiting bodies are formed, black (Fig. 2.15).

Control:

As with other brood diseases, the bees remove the infested brood with their hygiene behaviour, which is especially effective for white mummies. Though as soon as the fruit bodies of A. apis have developed, cleaning honeybees spread the spores within the colony by this behaviour.

During the white mummy stage, the fungus continues to develop at the hive bottom. If the mummies are not removed quickly, the spores may enter the brood cells carried there by circulating air. At early stages of chalkbrood infection, adding young adult workers into the hive and hatching brood, combined with sugar-syrup feeding, proves to be helpful.

Till now there is no known successful chemical control against chalkbrood. In most cases, commercialized substances only show a positive effect because they are sprayed, or fed with sugar water as described above.

Viral Diseases:

At least 18 virus types and strains have been recorded as pathogenic to adult bees and bee brood. Most of these are RNA viruses. The damage caused to colonies by viral infection varies considerably according to a number of factors, which include the type and strain of virus involved, the strength of the colony, weather conditions, season and food availability.

Among the viruses, Acute Paralyses Bee Virus (APBV) and Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) are becoming increasingly destructive. As not much is known about the life cycle and pathogenecity of most virus diseases, there are only a few ways to control them. Therefore, keeping this in mind, only the most widespread sacbrood is described.

Sacbrood disease:

The virus is native to the Asian continents and is known for a long period. It was first discovered in Thailand in 1981. Since then it has been reported to be present in association with A. cerana in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and all other countries of Asia.

Cause:

This disease is caused by Morator aetotulas and is perhaps the most common viral disease of honey bees. In Asia, at least two major types have been recorded. Sacbrood disease affects the common honeybee Apis mellifera and the Asian hive bee A. cerana. It is presumed that nurse bees are the vectors of the disease. Larvae are infected via brood-food gland secretions of worker bees.

Symptoms:

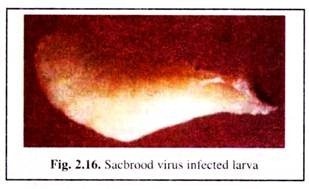

Diseased larvae fail to pupate after four days. They remain stretched out on their backs within their cells. The anterior section of the larva, consisting of its head and thorax, is the first part of its body to change colour.

It changes from white to pale yellow and finally to dark brown and black (Fig. 2.16). The skin of the larva becomes tough and internal organs become watery. The infected larva thus has the appearance of a small, watery sac.

Control:

Field inspection to determine whether the pathogenic virus has infected a colony can be easily carried out following symptoms. No chemotherapeutic agent is effective in preventing or controlling sacbrood disease. The recovery mainly depends upon the hygiene behaviour of the bees, which may be stimulated with other brood diseases.

The disease usually occurs when the colony is under stress, i.e., shortage of food, food-storage space, unfavourable climatic conditions (such as damp during the rainy or cold season), unhygienic hive interior, poor queen health, infestation with other diseases, etc.

In severe cases, requeening the colony, removing infected brood combs and taking other management measures to restore colony strength, such as providing food and adding worker population generally gives good result.

Protozoan Diseases:

Nosema disease (Nosemosis):

Nosema disease is generally regarded as one of the most destructive diseases of adult bees, affecting workers, queens and drones alike. Seriously affected worker bees are unable to fly and may crawl about at the hive entrance or stand trembling on top of the frames.

The bees appear to age physiologically. Their life-span gets much shortened and their hypo- pharyngeal glands deteriorate – the result is a rapid dwindling of colony strength. Other important effects are abnormally high rates of winter losses and queen super-sedures.

Cause:

The disease is caused by the protozoan, Nosema apis, whose spores infest the bees and are absorbed with the food. It germinates in the mid-gut. After penetration into the gut wall the cells multiply forming new spores that infect new gut cells. The nutrition of the bees is impaired, particularly protein metabolism.

Symptoms:

In severe cases of infection, the abdomen of an infected worker becomes swollen and shiny in appearance. On dissection, the individual circular constrictions in the alimentary canal of uninfected bees are clearly visible, while the constrictions cannot be seen clearly in diseased bees.

The most reliable method of detecting Nosema disease involves laboratory procedures using a microscope for diagnosis. The bees are killed, and their abdomens are removed and ground in water (2 to 3 ml per sample). A drop of the suspension of pulverized bee abdomens is then viewed under a microscope.

If the disease is present, reasonably large individual bacilliform spores with bright, fluorescent edges will be observed. The microscopic inspection of queen’s faeces makes it possible to verify the presence or absence of the disease.

Control:

Nosema can best be controlled by keeping colonies as strong as possible and removing possible causes of stress. Colonies and apiaries should receive adequate ventilation and protection from cold and humidity. The bees should have the possibility of foraging regularly in order to defecate. This prevents spreading of the spores within the colony.

Beekeepers should also ensure that their colonies and queens come from disease-free stock. Hive equipment that is suspected of being contaminated by Nosema apis spores should be thoroughly decontaminated, preferably by heat and fumigation.

The only effective chemotherapeutic method currently available for treating Nosema is to feed the colony with fumagillin (25 mg active ingredient per litre of sugar syrup), preferably at a time when the colony is likely to encounter stress conditions, such as during a long winter or rainy season.

The active ingredient of fumagillin is an antibiotic. It is of utmost importance that no medication be administered to colonies when there is a chance of contaminating the honey crop.